His Last Appearance

By

H. BEDFORD-JONES

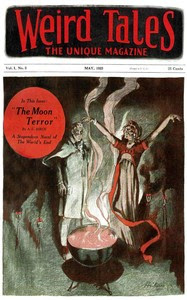

First published Weird Tales, July 1943.

What makes this country you revere?

Not trees and earth and citied roar

And ways of life—but something more:

Voices that rise from far and near,

Voices of those who went before

And gave their lives by field and shore.

What makes this fatherland you love?

Not prating words nor gestures grand,

But you yourself. Your soul’s command,

Stern self-denial (faith above

All else), your strength of heart and hand—

These go to make your fatherland.

Gordon sat looking out across the reefs and the blue sparkling Pacific, from which the last vestiges of war had vanished half a year ago.

The great Brisbane Clipper, instead of pausing here in mid-Pacific to refuel, was moored to the floats; a hurricane somewhere over the horizon ahead had halted her. The passengers were occupying the little rest-house. There was nothing on this bare coral islet except the hangars and sheds, the workers’ quarters and shops, the rest-house and the radio and weather station, and a few isolated graves left over from war days.

Gordon was a tough citizen, hard as rock and with as much sentiment in him as a block of granite might have. During the war he had worked up to top place in the shipyards. After the sudden Nazi collapse he had piled up money, shrewdly, and got into politics. It was Gordon, they say, who was partly responsible for winning the Japanese war; it was he who hammered away until the policy of cutting off the octopus tentacles was abandoned and the bombing fleets wiped the Jap cities off the earth’s face. He got no credit for it; he had few friends and was well hated in many quarters. He had the heart of a crocodile, and the sympathetic appeal of an iceberg, by all accounts.

Now he was on a sight-seeing tour of the world, the great new world slowly emerging from its war-agonies. His flinty features, his bitter hard eyes, showed no kindliness for anything or anyone. Back in the shipyards they used to call him “Rock” Gordon; usually they added another word to it.

Such was the man who sat on the wide veranda of the rest-house and chewed at an unlighted cigar and sipped a long cool drink.

One of the Clipper pilots came out of the doorway and paused beside Gordon, who indicated two white objects at a projecting point of the island.

“What are those white things?”

“Grave markers,” said the Clipper man. “Two Flying Fortress chaps are buried there, Cox and Magruder. They landed here during the war; quite a story to it. The Nips wiped ’em out, finally. At low tide, on the left of the channel, you can see what’s left of a Jap destroyer they perforated.”

“Why weren’t they taken home for burial?” snapped Gordon.

“Seems like they wanted to stay here; nothing but coral rock to bury ’em in, but they liked it. When we retook the island, later, we found a notebook they had written in, asking to be buried here if they were killed. Apparently they had worked up an affection for the place, God knows why! They’re the ones who named it Coral Territory.”

“Affection for this blistering hole!” sniffed Gordon. “Isn’t likely.”

“You never know. The mechanics here tell some darned funny stories; they claim that Cap’n Magruder sticks around here. Even in full daylight. Some swear they’ve seen him.”

“Rot!” said Gordon scornfully. “Show me a photo of a ghost and I’ll believe it, maybe.”

The pilot laughed. “Well, you give a chap three months on this coral reef, and he goes nuts; he can see anything. One of the men even claimed he had talked with Magruder’s ghost. And you’d be surprised how many folks take it seriously. Some cockeyed geezer back home wrote it up in a magazine, claiming that a reef like this in the middle of the ocean was an ideal place for occult manifestations, as he called it. Something about vibrations or frequencies; I don’t savvy it, myself.”

Gordon merely grunted disdainfully, and the pilot went his way, thankful to escape silly questions about how soon the Clipper would get off.

Some time passed. Gordon was not in the least sleepy; his tremendous energy needed little sleep. And he seldom drank; this gin-and-bitters was his only drink today. His head was perfectly clear. In fact, he was thinking about a big business deal he could put through by radiogram. He glanced at his watch, computing the difference in time between here and San Francisco. He was on Pacific time here; it was precisely three o’clock. He remembered to wind his wrist-watch. As he was doing it, an officer came up the steps and nodded to him. His was a strange face to Gordon; probably, he thought, one of the men stationed here.

“Like to look around the place?” asked the stranger.

“Too hot,” grunted Gordon. The other laughed. He was a boyish-looking young chap, and oddly enough wore an army uniform, flier’s wings and the insigna of a captain.

“It was a lot hotter when we came. Just a year ago today, three o’clock. How’d you like to turn the time back? It might be done, with a man like you. When a chap has a lot of vitality, things like that can happen.”

“I don’t get you,” growled Gordon. The other lit a cigarette, smilingly.

“No, I expect you don’t. But you will. This island is a wonderful place, really! It’s a part of the United States now, you know; the Congress enacted it, just after the war, on account of the things that happened here. Sort of a public monument, like the National Parks at home.”

Gordon was not interested, and merely grunted. The other rattled on lightly.

“Grand ship, that Clipper yonder! Y’ know, we came here in a Fortress; one of the old B type, without guns in the belly and tail. She was good, though. That was just after Pearl Harbor. We were making for Manila, and ran slap into a hell of a Jap flotilla and their planes came up at us. My ship got it hot and heavy, we lost contact, and that’s how we happened to come down here—”

This was the last Gordon remembered, later. He seemed to merge somehow with the man talking to him; everything seemed to merge. The Clipper vanished. The boats and the rest-house itself disappeared. Nothing was left except a few sheds, and a big plane that sat on the coral sand near the sheds. It was a Nakashima, an old type of Jap naval plane, and a group of Japs were working around it.

The Fortress had no choice; she came down in a long, straight dive, with blood leaking out of her. Ack-ack fire had played the devil with her. Magruder had the controls, his boyish features white and set and strained. He was unhurt, but his co-pilot was dead. The radio man and his radio were blown all to hell. None of the crew was alive except Cox, the bombardier, and the burly sergeant-mechanic, Griswold.

Magruder would have preferred that any of the others might have traded places with Cox. Neither he nor Cox had much use for each other. However, all that was in the past. Magruder looked at his gauges; the gas tanks damned near empty. The line must have been cut somewhere. Well, he had plenty to do his work here and get down.

The Fortress shivered. A white burst showed close by; others blossomed behind. The Japs down below had seen her. An ack-ack gun was whipping away down below. Men were frantically getting into the Nakashima and trying to get her up. Magruder laughed at that. Small chance! That Nip fighter was his meat now.

The two remaining engines roared full; two had been shot dead. The Fortress swooped and circled, and her guns jetted flame. A crazy hysteria had taken hold of Magruder. When the Nakashima burst into flame, he went after the gun crew and they were wiped out. Then he got after the running, screaming, panicked Japs who were breaking for cover. More bursts swept them. Magruder ran them down like grounded pigeons. He ducked and swooped and banked all over the coral reef and back again, killing Japs. He had already heard what these Nips had done to the Clipper people when they took over this coral islet.

Then a wild hope seized him. There must be fuel here—he might be able to get away with the patched-up Fortress! That is, if he could land her. There was something wrong. That shell-burst had smashed something—his controls would not respond—

She crashed, and did a beautiful job of it, but not till Magruder had cut the switch. The crash knocked him silly; the whole front end was a twisted wreck.

Cox and Griswold got him out the hatch. He came out of it in no time and was quite all right. The three sat down on the hot coral, got rid of needless equipment, and lit up cigarettes.

“Well, we’re here,” said Magruder, looking around. The Nakashima was burning and sending up a pillar of smoke. Not a living thing was in sight.

“Any orders, sir?” asked Griswold. Magruder shook his head. “Then I’ll take a look around. Might be able to clap a bandage on some of these Japs.”

“After a fifty-caliber bullet hits, they don’t need a bandage,” said Cox. Griswold grinned, slapped his holstered pistol, and sauntered away. Magruder sat with his head swimming, until Cox brought him out of it with a quiet remark.

“Nice landing we made, Cap’n. Looks like it washed up Betsy for keeps.”

Betsy was the Fortress.

“Lucky to make any landing at all,” said Magruder. “And you’d better keep a civil tongue in your head.”

“Oh!” chirped Cox. He was a little fellow, full of ginger. “And I s’pose you’d like to be saluted every hour, and have me promote your meals and your coffee and keep your boots shined? Like hell I will! You’re nothing but a pilot now, and a lousy one.”

Magruder came from Portland, and Cox from Seattle, and neither of them forgot it.

“You’ve needed a poke in your sour puss for a long time, and now you get it,” said Magruder, standing up. “And—”

He was cut short by the sharp, heavy report of a shot, then another, then several all at once. Both men swung around. Sergeant Griswold, halfway up the island, had run into three Nips hiding in a crevice of the coral, and they were not dead. Magruder broke into a run, but Cox outran him, lugging out his service pistol.

By the time Magruder got there the last Nip was dead, but so was Griswold. They had plugged him as he came up. Magruder looked down at Griswold, his face working, then up at Cox.

“Damn it!” he said. “Look, Coxy, let’s forget everything.”

Cox put out his hand, and they shook. Cox and Griswold had been great pals.

“You know,” said Cox, “we got a lot of work to do. Burying.”

“Yeah,” said Magruder. “Let’s make sure of these Nips, first.”

They fell to work searching, but those .50 machine-gun bullets had played no favorites. Their only job was to get rid of the bodies, which were simply slid into the water on the ebb tide. It was different with Sergeant Griswold and the rest of the crew of the Fortress; they were boxed and laid in the sand above high tide. This job took the two of them through the night and most of the next day.

There was no lack of material for boxes. All the stores and materials of the Clipper people were here and the Nips had landed a lot besides; it looked, thought Magruder, as though the base were to be permanently held, which meant that more Japs would be along. Not a pleasant reflection.

This fear quite spoiled what would have otherwise been an adventure worth while.

The radio station had been wrecked by shellfire when the Japs took over the islet; repairs were under way, but there was no hope of using the outfit. The Fortress radio was nothing but ragged fragments, like Betsy herself. They salvaged two of their machine-guns but were low on ammunition.

Water and food supplies were ample. The shops and other buildings had also been shelled to bits, though rebuilding had begun. Stock piles of gasoline and fuel oil, all made in the U.S.A., were under the sheds.

“Y’know, we could stay here a long while and just take sun-baths,” said Cox on the second evening, relaxing after that hard day’s work.

“That is, if nobody else came along.”

“You said it, Cap’n. When do you look for ’em?”

“Tomorrow or next week or next month,” said Magruder lazily. “Our first job is to get organized for defense. We’re out of the air but still at home.”

“What d’ye mean, home?”

“Well, this is part of our country, isn’t it? The guys that were here when the Nips came, put up a hell of a fight; they’re dead or eating rice and fish-heads now. I’d sooner be dead than on that starvation diet. Yes, this island is U.S. soil, sure enough.”

“Not the kind of soil we got around Seattle,” said Cox, eyeing the snowy coral sand. “Maybe it reminds you of Portland; they got a lot of sand up that way.”

“No argument, Coxy,” returned Magruder, refusing the challenge. “We got to stick together, bud. The Sarge checked out here; but before him—think of those guys the Nips caught! No graves around; they must have been fed to the fish, too. Well, that helps all the more to make this U.S. ground.”

“Oh, I get the idea now,” said Cox. “Does make it easier to think of it that way, sure! We get to beefing about back home—well, this is part of home, sure! The old U.S. has reached out a hell of a ways to get here, though. Y’know, I’d like to see one of them whistling Navy planes coming down the sky.”

“What you’ll see is something else sooner, I reckon.”

“And when we run out of cigarettes?”

“Use what we took off those Nips. Maybe we’ll find some in the stores, too.”

Now began sunny, endless days of preparation against the worst. For two men to even dream of beating off any Jap force that might come, was fantastic; and yet some fantastic things had been done in this war.

Magruder had two things in mind; first defense, and second emplacement. They had two heavy machine-guns off Betsy but mighty little ammunition; a number of Tommy-guns with boxes of cartridges, and a beautiful Jap machine-gun of lighter caliber, of the type invented by a White Russian refugee, that will not overheat. There was a battery of ack-ack emplaced, but only half a dozen shells left for same; practically useless.

In a newly-built emplacement, however, was installed a three-inch quick-firing gun, with case after case of ammunition to hand. The Japs had obviously been aiming to install an entire battery of these guns here, but only one had arrived. The situation for it was superb, commanding the reefs and the one channel of approach, and indeed the entire islet.

Magruder consulted with the bombardier.

“We only got one gun crew, and that’s me,” said Cox, grinning cheerfully. “So you praise the Lord and I’ll pass the ammunition. I reckon I can serve that three-inch baby, though those shells aren’t peanuts by any means. Better keep that Jap machine-gun for close quarters. You figure on planes strafing us?”

“Figure on everything,” Magruder said. “If we hold off till a plane’s right on top of us, we might get her with the ack-ack; otherwise not. What scares me is the idea of a landing party.”

“It ain’t nice to think of, for a fact; not half as nice as the Seattle waterfront,” observed Cox, “But if it happens, I reckon we’ll raise some hell before we go under. Look what I found in Griswold’s stuff!”

He unfolded a Stars and Stripes of silk, which ran to some size.

“Don’t hoist it now,” said Magruder. “If the Nips do show up, we want to do our first advertising with bullets.”

They decided to plant the two heavy machine-guns close to the water, after careful plotting out where any landing party might be expected to come ashore. Well back of these they got to work building a barricade of coral chunks, deciding to place the Jap gun here; this was a labor of some days.

The monotony here was frightful—monotony of sea and sky, of coral sand, of food, of each other. A week of it had Magruder’s nerves ragged and Cox yapping at him like a terrier. They came to blows, but in the midst of a battle royal sober sense came back to them both at the same moment; they sheepishly abandoned the scrap and went for a swim, and this was a lesson. They drew more together after this, appreciated each other more.

“What you said about this being a part of home,” observed Cox one evening, “kind of grows more true all the time. U.S. soil, I mean. It feels that way, somehow. My folks live in Seattle, and I had a job at Olympia till I went into the army. This is nothing like that country, and yet I got the feeling that this is part of home, too.”

“So it is,” assented Magruder. “That’s because men died here to hold it, our men. Just a naked little coral reef, of course, but it was part of the great Clipper adventure. It wasn’t worth anything till we took it in, but now its worth a hell of a lot, same as Midway and Guam and the rest. I’m glad you’ve got that U.S. flag to run up. We won’t have an earthly chance if the Japs do come, you know.”

“Shucks! No bullet’s got my name on it,” declared Cox scornfully.

“How do you know?”

“Fortune-teller told me so. I’ve got a real long life-line.”

Magruder made no comment. It was a good feeling to have; he wished he could feel the same.

“Fine and healthy for us here, anyhow, even if the grub’s monotonous,” he said cheerfully. “Only one thing I do wish—that’s for some earth, real earth. This blasted coral rock and sand isn’t real. Gets on my nerves sometimes.”

“That’s right,” said Cox. “Earth with worms in it, huh? Say, you know—if this is part of our country, what state does it belong to?”

Here an argument started and it went far. They finally decided that the island was a territory all to itself, like Hawaii or Alaska; that stood to reason, said Cox.

With morning they began a game that sounded silly yet was serious. They named the island, whose name was unknown to them; they called it Coral Territory. They went over it yard by yard and named the reefs and bays, then went on to divide it up into various portions—a statehouse here, a courthouse there.

This game lasted for two days, until Cox broke down and put his face in his arms and bawled. Magruder comforted him; it was sheer loneliness, empty sea and sky that got on the nerves. They ended up by laughing in unison.

They had neglected to keep track of time, but figured it was a trifle over two weeks from the day they came down, when one morning Magruder was up and yelling, and Cox joined him, and they hurriedly made a bonfire of scrap they had collected. A plane, a whistling Navy plane sure enough, as the queer radio-like whistle of her struts sounded. But she was high and far, a mere silvery fleck in the sunrise; she passed and was gone, and in silence they beat out the smoke signal.

Yet, where one was, might come others; this hope gave them a lift.

“That soil you talked about one night, with earth worms,” Cox said abruptly upon a day, as they dried off in the hot sun after swimming. “I been thinking about it. I’d like to see some of it, too. Earth, with moss on it, and maybe a sapling starting up green. You know there’s not one blessed green thing here?”

“That’s a fact,” said Magruder, nodding. “If there was any earth, there’d be green things sprouting, you bet! You take that little headland of coral, up there just past Radio City—that’d be a swell place to plant Griswold, if there was just some real dirt soil to do it in! You’d see trees there in no time.”

“If there was water, which there ain’t,” said Cox, dreamily. “I’m getting sort of tired of this here canned water.”

“Well, it’s good water anyhow.”

“Yeah, but I bet them drums had oil or gas in ’em once, by the taste. Hello, tide’s out! Let’s go get us a fresh pan fry.”

Low tide brought riches, as always, for the reef pools often held all sorts of fish, but today Magruder cut his foot on the coral, a bad cut. Cox got out Betsy’s first-aid kit and Magruder was almost glad of the injury, since it made a welcome break in the overwhelming monotony of life. But he had to hobble.

Among the meager effects of the Japanese who had been here, they discovered a tiny portable phonograph. At first they disdained it; later on the thing became a life-saver. The only records were, of course, in Japanese, but two of them were music. Cox got the idea of inventing a dance to go with this alleged music, and they cavorted about by the hour in rather crazy attitudes and steps. It was exercise, and it did help to break the time, but Magruder found that accursed music imprinted on his brain and so finally called a halt.

They summoned up every aid of imagination and invention to make a spot in the unending hours. They played war games chiefly, imagining landings at various parts of Coral Territory and working up skill in serving the guns. Since there was abundance of shells for the three-inch, they even got in some practice with it, also with the light machine-gun. The tommy guns, with drums of ammunition ready, were placed here and there for quick reference in case of attack. There were some rifles, with no end of .25 caliber cartridges, but these they disdained.

Cox got a staff rigged with the silk flag, ready to run up either to call for help or to speak defiance. Also, mindful of how they had picked off the running Japs, Magruder got out everything white he could find, for coverage.

“If they do come, our cue is to lie doggo,” he said. “Uniforms show up too plain against this white coral and sand. Funny thing is, if there were two hundred of us we’d find ourself in hot water, but just two men—well, Hirohito wouldn’t pay any heed to ’em.”

“Three,” said Cox. Magruder gave him a look of inquiry. “The Sarge. He’s sticking around, isn’t he?”

“I don’t know, and neither do you.”

“Sure I do!” asserted the bombardier. “The Sarge loved Betsy like a child. You can bet he’s hanging around her right now. And those other guys who were here in the first place. All of ’em. Coral Territory is part of our country, isn’t it? When a guy gets bumped off in these parts, where else can he go?”

This frightened Magruder. He was wise enough not to argue about it; Cox had an absolute fixed idea on the subject. Magruder himself, at times, was tempted to absurd thoughts and illusions, but fought resolutely against them. He hoped Cox would not go dotty about ghosts.

One day a queer thing happened. Their own yellow rubber boat, which was automatically released when the hatch was opened, had been ripped to pieces in the crash; not even the repair kit availed to make her serviceable. But, of an afternoon, a speck of yellow grew on the sea and came drifting in upon the tide, bobbing right along with the current that swept among the reefs. It was some other aviator’s rubber boat, and it was inflated; the attached bottle of CO2 had been used, and the packet of emergency rations was missing. Nothing to tell where it came from.

There was something gruesome and terrible about this arrival from nowhere and far more so when Magruder figured out its story. They turned the “doughnut” over and saw a lot of small patches along the edges and bottom. The repair kit had been just about used up putting them in place.

“No telling where it came from; must have come a long way,” he said, looking down at the thing with darkening eyes. His bronzed features were grave. “But this chap had one hell of a time.”

“How you figure that?” demanded Cox.

“He landed all right somewhere at sea; the rations are gone, but he didn’t starve to death. See those patches? We’ve heard plenty about how sharks like these yellow doughnuts—how they rub against ’em and nibble at ’em. That’s what happened here. The CO2 flask is empty, too—not a sizzle in it.”

“I don’t get the idea,” said Cox, puzzled.

“Well, a shark nibbled. To repair the hole, this guy had to slip into the sea and work. Happened nearly a dozen times. That damned shark must have stuck right with him. See what would have happened to us if we’d come down at sea? This guy either got grabbed just after he had fixed the last hole, or else he went off his nut completely and slid overboard, and the shark got his meal and quit.”

Cox shivered. He stared at the doughnut with brooding eyes.

“I expect you’ll claim the thing got here by accident,” he observed. “But it didn’t. It was steered here. That guy was making for the nearest U.S. soil, and this is it, pard. Probably the Sarge went out to meet him and helped fetch it here. No, sir, this was no happenstance! You can’t tell me it was.”

Magruder swallowed hard, but proffered no objections. Never argue with a screwy guy; it only makes him worse.

“Well, now we’ve got a boat, so we can paddle around and do some fishing,” he said.

A bright thought. For the next two days they did little except make use of the rubber boat; once they blew off the island and had the devil’s own time paddling back. There were no sharks about, luckily.

“I guess this place must be quite a rendezvous for guys who have passed out,” said Cox, as they were shaving on the third morning. “If we only could see them, there must be a crowd hanging around. Coral Territory would have a big voting list—”

“Lay off it, will you? Lay off!” broke out Magruder.

“Okay,” said Cox, surprised but complaisant. He strolled off toward the shore, then came back on the hop. “Hey! Why did you deflate the doughnut?”

“I didn’t.”

“Well, somebody did. She was blown up last night and now she’s flat as a pancake!”

Magruder hurried along with him. Sure enough, the rubber boat was flat and nothing to account for it.

“It’s a sign, that’s what,” Cox declared in his serious, matter-of-fact way. “I’ll bet the Sarge did it, or maybe the guy who fetched it here.”

“You’re nuts,” said Magruder, exasperated. “A sign of what?”

“Trouble. A sign that we’re not to budge out in that doughnut again.”

“Now look,” Magruder said patiently. “This coral is sharp as hell in spots. The rubber got chafed somewhere and sprang a leak, that’s all. We can blow her up a bit and put her under water like an inner tube, and find the spot by the bubbles. We’ve got the CO2 flask and the repair kit from our own outfit to use.”

Cox shook his head dubiously.

“You can if you like. Not me! We’d be in a fine fix if the Nips showed up while we were paddling somewhere off Cape Lookout or Radio City! No, sir, I know a sign when I see it. I’m going to load up that ack-ack gun right now and fill the belts on the machine-gun.”

“Better eat first,” snapped Magruder. “If you’re so darned certain about your sign, we’d better fill our bellies. I’ll have a porterhouse steak, nice and juicy, and not too well done, and a dozen eggs and some prime bacon. And don’t burn the toast.”

Cox grinned at this and grudgingly said breakfast might come first; and so it did.

Coral Territory was an unsteady sort of thing; it was always trembling. When the tide was on the make, the surf battered the long reefs ferociously, making the whole island shiver underfoot. The surf was worse than usual this morning, just now the tides being extra high.

Magruder went at the job of fixing the doughnut himself. Sure enough, he found a couple of spots where the coral must have chafed through the stout rubber, and he set about making repairs. It was quite a job, and he took the deflated boat up under shelter of the sheds, as the morning sun grew hotter. Cox’s fixed idea about ghosts weighed his mind heavily. Too bad, he thought, that the little fellow had these crazy notions. It was a bad sign. He glanced up and noted that Cox, sure enough, was pottering around with the artillery. For the two guns taken off Betsy they had fixed up finger triggers to replace the automatic triggers, and had made a neat job of it. Cox was quite an adept with tools.

Magruder was aching for a cigarette when he got the patches in place. They had agreed not to smoke around these sheds where the gas and oil and explosives were stacked; also, with no supplies on hand, they were low on cigarettes and rationed them at the rate of four per day per man. Only a dozen or so now remained.

Stepping out from the shade, Magruder took out his first cigarette of the day and was in the act of lighting it when he heard Cox yell. He looked up. The bombardier was standing beside the Betsy’s machine-gun nest and waving. Magruder swung around, took one glance at the horizon, and dived back to shelter of the shed. Cox likewise vanished, next instant.

She was coming in, not very high but fast, from the west. The morning sunlight etched her sharply as she came and distinctly showed the Jap insignia on wings and tail. Magruder, lying motionless, damned the binoculars that were not at hand; however, he could see her clearly enough. She was not large at all, just a tiny reconnaissance plane such as might be carried on any ship’s deck and catapulted off. He could see two dots of heads craning over the side; she was coming lower to examine the islet. Down to a scant hundred feet, he judged.

She gave a sudden upward jump and zoomed up and over; the sight of Betsy lying there must have been quite a shock to the Nips. On past the far end, she banked sharply and came back, again dropping low to investigate. The absence of all life on the islet no doubt encouraged her to closer examination.

Then, suddenly, one of the Betsy’s guns let go with a burst; that was Cox, unable to resist. The Jap was directly overhead at the instant, and before she was gone Cox gave her a second burst. Magruder, staring up, distinctly saw the heavy bullets ripping her apart. His heart jumped. He leaped to his feet, yelling frantically.

The plane never had a chance to take fire. She just dived; she came down in the water right off Radio City and kept going. The water closed over her and that was all. The two Nips went with her and stayed with her.

Magruder scrambled over to the guns and pounded Cox delightedly on the back. They yelled, stared at each other and the water, laughed together in wild delight.

“That’s one for Betsy,” said Cox. “I bet the Sarge is tickled about it!”

“Boy! You sure did it properly!” Magruder exclaimed. Then he fell sober. “Well, I guess you know what this means. She didn’t just come from nowhere.”

“You said it, Cap’n. Take a gander north by west.”

Magruder looked. Sure enough, a smudge of smoke showed on the horizon.

“Okay,” he said. “I’ll hand it to you for your sign, Coxy. Let’s get into our whites. And no use going easy on the cigarettes. Too bad you didn’t bring that Nip down on the coral—we’d have likely got some good smokes out of her.”

Cox grinned, though he was a bit pale around the mouth. He knew what was coming, all right.

“I expect we’d better use up that ack-ack ammunition first,” Magruder said as they got into their white duds. “That is, if there are no other planes around. Likely that one was carried on a ship and was the only one. They’ll guess there’s something wrong when she doesn’t report or show up; they’ll spot the Fortress, too.”

“Why the ack-ack gun, then?”

“Because she’s got a damned good range and those little shells are deadly; but they’re contact shells. If we can throw ’em into a ship, she’s a goner. They’d be no good against a landing party. Not enough of ’em. And then there’s the location of the gun, too, away from the others.”

He had figured this out carefully, the ack-ack gun, an imitation of a Brenn model, being placed well off to one side by itself. There were only seven shells left for her.

With the binoculars, they watched from the ruined radio station as the smoke first blossomed, then became a dot; then two dots. Being an army man and not a navy flier, Magruder had no training in distinguishing ships, but here he needed none. Two craft were headed for the island. One was a freighter of some size, the other was a destroyer. Both were Japanese.

“Betsy must feel mighty gloomy,” said Magruder, “to think of the fine big bull’s-eye Jap marking on the for’ard deck of that freighter, and her lying here helpless to get in the air! Well, bud, that makes it pretty clear. No more planes. A transport filled with men to get the works here in shape, and a destroyer.”

“Want to put up the flag?”

“Not yet. Not till we see if we can tempt them to come close. Once they know we’re here and fighting, they’ll shell the living guts out of Coral Territory.”

“What we want, then, is to get the destroyer if we can.”

Magruder made no answer, except a grunt, and looked at the wan moon, high in the sky. Most of the night and nights to come would be moonless; however, that three-inch gun had a range of five miles or so—in expert hands. No expert hands here.

“We’d better duck,” he said. “They’ll be watching.”

Their white rags grotesque in the sunlight, they came back to the ack-ack gun, which no longer pointed skyward. Those seven little conical shells made the heart sink, so puny were they. After putting them into one of the quick-firing holders, they lit cigarettes and waited, watching the water.

The destroyer was now coming well ahead of the freighter, evidently running in for a closer look at the island. The disappearance of that scouting plane must have puzzled the Nips considerably; but the immobile Fortress would be visible a long way off.

Oddly enough, Magruder felt unexcited, even a little depressed. Two men could not hope to do much of anything. He watched the destroyer as she came in toward the reef channel. Officers were clumped on her bridge, examining the shores; men were clumped about her guns fore and aft. She was ready for any trouble that might show itself.

“How far you want to let her come?” asked Cox hoarsely.

“Close as she’ll come,” replied Magruder. His mouth felt dry. “Once we use up those seven shells, you want to get to hell out of here. Over to the three-inch gun. That dugout she’s in will give us protection.”

“I’m a swell runner,” said Cox. “Glad I smashed Betsy’s bomb-sight. They won’t get that, even if they do get us.”

“Get ready to jump,” said Magruder, passing him the glasses. “Watch where the first shell lands, then lift or depress her. We won’t have any chance to play at range-finding. That twist in the channel, by the outer reefs, I figured at a thousand yards; she’s there now. The gun’s laid for five hundred, off that hummock of coral where we caught the devil-fish. Closer than that, she’d be coming ashore on us, so stand by.”

He dropped his cigarette and went to the gun, and waited, wishing he knew more about artillery. An expert hand would hit those Nips like a bolt from the blue before they knew what had happened!

The destroyer had slowed speed. The freighter or transport was standing off about three miles, he calculated, evidently awaiting word before coming along. The destroyer evidently knew these waters well, probably had been here before. She was heading straight for the central lagoon. She was off the hummock now; she was dead in the sights—

Magruder sighed and went to work. He was not happy about it. The gun banged and jumped. The fumes hid the result from sight.

“Over her!” Cox came with a yell and grabbed the depressing wheel. “Not much, but a little. There y’are—now give her hell!”

The destroyer was swinging around. The gun began to jump and the fumes hid her; Magruder fired the six remaining shells. He heard Cox yelling jubilantly, then scrambled up beside the bombardier and both of them legged it frantically for the cover of the dugout by the heavy gun. A shell exploded behind them, exactly beside the ack-ack gun; then hell broke loose all along the coral strand.

Before ducking for cover, Magruder looked at the destroyer; nothing seemed to have happened, but Cox was cursing and yelling in mad excitement. Then Magruder saw that something had indeed happened. The destroyer’s guns were belching smoke and flame, but she was swinging farther and farther, quite aimlessly. And the tide was on the ebb now.

“By gad, she’s going on that submerged reef!” yelled Cox. “That whole bunch of shells went into her stern, Cap’n! I could see ’em! She’s knocked out!”

A shell burst overhead and he ducked for cover.

The destroyer was giving all she had, while she had it to give. Her shells burst chiefly around the ack-ack gun, then searched out everything in sight. A tremendous detonation shook the very ground under their feet; Magruder looked, to see the oil and gas and munitions sheds going up in an inferno of fire and black smoke. Then Cox grabbed his arm.

“Look! She’s on the coral, heeling over—can’t bring her guns to bear—”

So she was. Down by the stern, she had struck the coral hard. They could see the men on the deck getting to their feet after the shock.

“Let’s go!” snapped Magruder. A burst of mad excitement went through him like an electric current. Both of them leaped for the three-inch gun controls. Like a wounded snake, striking frantically at nothing in blind ferocity, the destroyer was now sending a hail of machine-gun bullets at the island, giving the silent Betsy a thorough shooting-up. Through this conculsive madness the three-incher launched her shells, carefully, slowly, deliberately.

Magruder made two clean misses. By that time, lead was hurtling all around. Then the next shell went slap into her—and the next—and the next. Three in a row; then her decks lifted up in a tremendous burst of white, hiding her from view.

“That’s it,” said Cox hoarsely. “Steam; she’s gone up. Some of those Nips may come across the channel and get ashore. See you later.”

Magruder crawled out, watched Cox running and picking up a tommy-gun, and then sat down and looked at what had been the destroyer. It was unreal, incredible, past believing; but it was true. She was nothing but a hulk on the reef, vomiting black smoke and flame skyward. Finished, forever.

A few black dots appeared, swimming across the narrow channel. After a little, the chatter of Cox’s tommy-gun lifted vibrantly and angrily, then it fell silent. Nothing more happened. Dull explosions took place aboard the burning destroyer. Her bows blew out, then she just burned. Cox came walking back. He did not seem particularly happy.

“I guess it was a hell of a thing to do,” he said, then sat down and scowled at the water. “But hell! It had to be done.”

“All finished?” asked Magruder, and Cox nodded. “Yes, it had to be done, old scout, so cheer up.”

There was a whine in the air, a growing shriek like the trump of doom; they dropped flat, as a shell exploded fifty yards away. Now they remembered the freighter. She was firing a heavy gun and steaming away.

“She’s lighting a shuck for home!” cried Cox. Magruder shook his head, and looked again at the pale high moon, and sighed.

“No such luck. Just getting out of our range. You’ll see.”

They did. She lay well off, a mere dot, and sent shells hurtling in regularly, to burst everywhere and anywhere. And nothing else happened.

Magruder and Cox retired to the far end of the islet and stayed there. The smoke from the burning gasoline dump died out gradually. The destroyer smoked on by fits and starts. The shelling continued until the sun sank in red fury, then stopped.

“Now for it,” said Magruder. “Here’s the last cigarette; we’ll divide it. Better go back and see what we can find to eat before it comes.”

“Before what comes?” demanded Cox.

“Night. And landing barges.”

They sat waiting under the stars, by the two guns taken from Betsy. The coral was all shell-pits, the sheds were gone, the ack-ack gun was gone. The flag still blew where Cox had mounted it during the afternoon. Darkness crept down upon the waters, but smoke hazed everything; only, from the nearer reefs, ran flashes of phosphorescence like pale moonbeams along the water, as the surf broke. No light showed anywhere.

What happened, there under the stars and smoke? It was impossible to say; two men could not watch everywhere. Betsy’s guns ripped out for the last time; a wild frantic chattering and screaming came from barges creeping in upon the lagoon, then the ammunition gave out.

They used the light Jap machine-gun after this, but not long. Barges must have come in at several points. Other machine-guns began to rip and chatter from the right and from behind. Cox cried out something and tumbled on his face and lay in a heap. Magruder felt a shock, then another shock, and that was really all that he remembered about it, for there was no pain at all, nothing to remember afterward. He was quite emphatic on this point.

“That’s funny,” said Rock Gordon. “You know, I always thought it must hurt like everything to—”

He blinked in surprise and sat silent, for he was talking to no one. The officer with the flyer’s wings was not there at all; he was gone. Gordon looked around and found himself quite alone, the unlit cigar between his fingers. He frowned, shook himself, and looked at his watch, incredulous.

Four minutes past three! Four minutes had passed—why it was impossible! Yet the ice in his glass had not even melted. He lifted it and drank, and his hand shook a little.

“My God!” he said to himself. “Am I nuts or what?” There was no answer. He just sat there for a long while, looking out at the sun and the white coral and the reefs, and the iron framework of the Jap destroyer that showed at low water.

Gordon located the Clipper captain that evening, and handed him a radiogram.

“I wish you’d get this off for me,” he said. “It’s to the general manager of your line. Is it clear?”

The pilot glanced over the message. Astonishment came into his face.

“Good Lord, Mr. Gordon! Oregon earth—a ton of Oregon soil shipped here and put around those graves—why, do you know what that will cost?”

Gordon’s flinty features hardened.

“Cost be damned!” he snapped. “Can it be done?”

“Yes, I suppose it can. But there’s no necessity of that; the graves are well protected and cared for—”

“No necessity?” broke in Gordon, his words like bullets. “No necessity of anything, where dead men are concerned. That’s the trouble with people like you, from Congress down. When a man’s dead, there’s no necessity of anything. Well, I want those two boys reburied in Oregon earth; I want a ton of it brought here and the job done properly, and I’ll pay all expenses. And if anybody asks you why, the answer is that both Cox and Magruder would like it, and by God that’s answer enough!”

So it was, too.

About the Author

Henry Bedford-Jones (1887-1949) was a Canadian born author. Born in Napanee, Ontario, his family moved to the United States when he was a teenager and he eventually became a naturalized citizen. He was a prolific author of over 1200 short stories and about 100 novels, many of them set in the adventure theme. He contributed to several series for juvenile readers. Some of his stories ventured into the fantasy and horror genres. (Encyclopedia of Science Fiction)

H. Bedford-Jones at Amazon

.jpg)

.jpg)