For Scalp-prickling Thrills and

Stark Terror, Read

The

DEAD MAN'S TALE

By Willard E. Hawkins

The curious narrative that follows was found among the papers of the late Dr. John Pedric, phychical

investigator and author of occult works. It bears evidence of having

been received through automatic writing, as were several of his

publications. Unfortunately, there are no records to confirm this

assumption, and none of the mediums or assistants employed by him in his

research work admits knowledge of it. Possibly—for the Doctor was

reputed to possess some psychic powers—it may have been received by him.

At any rate, the lack of data renders the recital useless as a document

for the Society for Psychical Research. It is published for whatever

intrinsic interest or significance it may possess. With reference to the

names mentioned, it may be added that they are not confirmed by the

records of the War Department. It could be maintained, however, that

purposely fictitious names were substituted, either by the Doctor or the

communicating entity.

They

called me—when I walked the earth in a body of dense matter—Richard

Devaney. Though my story has little to do with the war, I was killed in

the second battle of the Marne, on July 24, 1918.

Many times, as men were wont to do who felt the daily, hourly

imminence of death in the trenches, I had pictured that event in my mind

and wondered what it would be like. Mainly I had inclined toward a

belief in total extinction. That, when the vigorous, full-blooded body I

possessed should be bereft of its faculties, I, as a creature apart

from it, should go on, was beyond credence.

The play of life through the human machine, I reasoned, was like the

flow of gasoline into the motor of an automobile. Shut off that flow,

and the motor became inert, dead, while the fluid which had given it

power was in itself nothing.

And so, I confess, it was a surprise to discover that I was dead and yet not dead.

I did not make the discovery at once. There had been a blinding

concussion, a moment of darkness, a sensation of falling—falling—into a

deep abyss. An indefinite time afterward, I found myself standing

dazedly on the hillside, toward the crest of which we had been pressing

against the enemy. The thought came that I must have momentarily left

consciousness. Yet now I felt strangely free from physical discomfort.

What had I been doing when that moment of blackness blotted

everything out? I had been dominated by a purpose, a flaming desire——

Like a flash, recollection burst upon me, and, with it, a blaze

of hatred—not toward the Boche gunners, ensconced in the woods above,

but toward the private enemy I had been about to kill.

It had been the opportunity for which I had waited interminable

days and nights. In the open formation, he kept a few paces ahead of me.

As we alternately ran forward, then dropped on our bellies and fired. I

had watched my chance. No one would suspect, with the dozens who were

falling every moment under the merciless fire from the trees beyond,

that the bullet which ended Louis Winston's career came from a comrade's

rifle.

Twice I had taken aim, but withheld my fire—not from indecision,

but lest, in my vengeful heat, I might fail to reach a vital spot. When I

raised my rifle the third time, he offered a fair target.

God! how I hated him. With fingers itching to speed the steel

toward his heart, I forced myself to remain calm—to hold fire for that

fragment of a second that would insure careful aim.

Then, as the pressure of my finger tightened against the trigger, came the blinding flash—the moment of blackness.

Ihad evidently remained unconscious longer than I realized.

Save for a few figures that lay motionless or squirming in agony

on the field, the regiment had passed on, to be lost in the trees at the

crest of the hill. With a pang of disappointment, I realized that Louis

would be among them.

Involuntarily I started onward, driven still by that impulse of burning hatred, when I heard my name called.

Turning in surprise, I saw a helmeted figure crouching beside

something huddled in the tall grass. No second glance was needed to tell

me that the huddled something was the body of a soldier. I had eyes

only for the man who was bending over him. Fate had been kind to me. It

was Louis.

Apparently, in his preoccupation, he had not noticed me. Coolly I raised my rifle and fired.

The result was startling. Louis neither dropped headlong nor

looked up at the report. Vaguely I questioned whether there had been a

report.

Thwarted, I felt the lust to kill mounting in me with redoubled

fury. With rifle upraised. I ran toward him. A terrific swing and I

crashed the stock against his head.

It passed clear through! Louis remained unmoved.

Uncomprehending, snarling, I flung the useless weapon away and

fell upon him with bare hands—with fingers that strained to rend and

tear and strangle.

Instead of encountering solid flesh and bone, they too passed through him.

Was it a mirage? A dream? Had I gone crazy? Sobered—for a moment

forgetful of my fury—I drew back and tried to reduce the thing to

reason. Was Louis but a figment of the imagination—a phantom?

My glance fell upon the figure beside which he was sobbing incoherent words of entreaty.

I gave a start, then looked more closely.

The dead man—for there was no question about his condition, with a bloody shrapnel wound in the side of his head—was myself!

Gradually the import of this penetrated my conciousness. Then I realized that it was Louis who had called my name—that even now he was sobbing it over and over.

The irony of it struck me at the moment of realization. I was dead—I was the phantom—who had meant to kill Louis!

I looked at my hands, my uniform—— I touched my body. Apparently,

I was as substantial as before the shrapnel buried itself in my head.

Yet, when I had tried to grasp Louis, my hand seemed to encompass only

space.

Louis lived, and I was dead!

The discovery for a time benumbed my feeling toward him. With

impersonal curiosity, I saw him close the eyes of the dead man—the man

who, somehow or other, had been me. I saw him search the pockets and

draw forth a letter I had written only that morning, a letter addressed

to——

With a sudden surge of dismay, I darted forward to snatch it from his hands. He should not read that letter!

Again I was reminded of my impalpability.

But Louis did not open the envelope, although it was unsealed. He

read the superscription, kissed it, as sobs rent his frame, and thrust

the letter inside his khaki jacket.

"Dick! Buddie!" he cried brokenly. "Best pal man ever had—how can I take this news back to her!"

My lips curled. To Louis, I was his pal, his buddie. Not a

suspicion of the hate I bore him—had borne him ever since I discovered

in him a rival for Velma Roth.

Oh, I had been clever! It was our "unselfish friendship" that

endeared us both to her. A sign of jealousy, of ill nature, and I would

have forfeited the paradise of her regard that apparently I shared with

Louis.

I had never felt secure of my place in that paradise. True, I

could always

awaken a response in her, but I must put forth effort in order to do so.

He held her interest, it seemed, without trying. They were happy with

each other and in each other.

Our relations might be expressed by likening her to the water of a

placid pool, Louis to the basin that held her, me to the wind that

swept over it. By exerting myself, I could agitate the surface of her

nature into ripples of pleasurable excitement—could even lash her

emotions into a tempest. She responded to the stimulation of my mood,

yet, in my absence, settled contentedly into the peaceful comfort of

Louis' steadfast love.

I felt vaguely then—and am certain now, with a broader

perspective toward realities—that Velma intuitively recognized Louis as

her mate, yet feared to yield herself to him because of my sway over her

emotional nature.

When the great war came, we all, I am convinced, felt that it would absolve Velma from the task of choosing between us.

Whether the agony that spoke from the violet depths of her eyes

when we said good-by was chiefly for Louis or for me, I could not tell. I

doubt if she could have done so. But in my mind was the determination

that only one of us should return, and—Louis would not be that one.

Did I feel no repugnance at thought of murdering the man who

stood in my way? Very little. I was a savage at heart―a savage in whom

desire outweighed anything that might stand in the way of gaining its

object. From my point of view, I would have been a fool to pass the

opportunity.

Why I should have so hated him—a mere obstacle in my path—I do

not know. It may have been due to a prescience of the intangible barrier

his blood would always raise between Velma and me—or to a slumbering

sense of remorse.

But, speculation aside, here I was, in a state of being that the

world calls death, while Louis lived—was free to return home—to claim

Velma—to flaunt his possession of all that I held precious.

It was maddening! Must I stand idly by, helpless to prevent this?

Ihave

wondered, since, how I could I remain so long in touch with the

objective world—why I did not at once, or very soon, find myself shut

off from earthly sights and sounds as those in physical form are shut

off from the things beyond.

The matter seems to have been determined by my will. Like weights

of lead, envy of Louis and passionate longing for Velma held my feet to

the sphere of dense matter.

Vengeful, despairing, I watched beside Louis. When at last he

turned away from my body and, with tears streaming from his eyes, began

to drag a useless leg toward the trenches we had left, I realized why he

had not gone on with the others to the crest of the hill. He, too, was a

victim of Boche gunnery.

I walked beside the stretcher-bearer when they had picked him up

and were conveying him toward the base hospital. Throughout the weeks

that followed I hovered near his cot, watching the doctors as they bound

up the lacerated tendons in his thigh, and detail of his battle with

the fever.

Over his shoulder I read the first letter he wrote home to Velma,

in which he gave a belated account of my death, dwelling upon the glory

of my sacrifice.

- "I have often thought that you two were meant for each other [he wrote] "and

that if it had not been for fear of hurting me, you would have been his

wife long ago. He was the best buddie a man ever had. If only I could

have been the one to die!"

Had I known it, I could have

followed this letter across seas—could, in fact, have passed it and, by

an exercise of the will, have been at Velma's side in the twinkling of

an eye. But my ignorance of the laws of the new plane was total. All my

thoughts were centered upon a problem of entirely different character.

Never was hold upon earthly treasure more reluctantly

relinquished than was my hope of possessing Velma. Surely, death could

not erect so absolute a barrier. There must be a way—some loophole of

communication―some chance for a disembodied man to contend with his

corporal rival for a woman's love.

Slowly, very slowly, dawned the light of a plan. So feeble was

the glimmer that it would scarcely have comforted one in less desperate

straits, but to me it appeared to offer a possible hope. I set about

methodically, with infinite patience, evolving it into something

tangible, even though I had but the most indefinite idea of what the

outcome might be.

The first suggestion came when Louis had so far recovered that

but little trace of the fever remained. One afternoon, as he lay

sleeping, the mail-distributor handed a letter to the nurse who happened

to be standing beside his cot. She glanced at it, then tucked it under

his pillow.

The letter was from Velma, and I was hungry for the contents. I

did not then know that I could have read it easily, sealed though it

was. In a frenzy of impatience, I exclaimed:

"Wake up, confound it, and read your letter!"

With a start, he opened his eyes. He looked around with a bewildered expression.

"Under your pillow!" I fumed. "Look under your pillow!"

In a dazed manner, he put his hand under the pillow and drew forth the letter.

A few hours later, I heard him commenting on the experience to the nurse.

"Something seemed to wake me up," he said, and I had a peculiar

impulse to feel under the pillow. It was just as if I knew I would find

the letter there."

The circumstances seemed as remarkable to me as it did to him. It might be coincidence, but I determined to make a further test.

A series of experiments convinced me that I could, to a very

slight degree, impress my thoughts and will upon Louis, especially when

he was tired or on the borderland of sleep. Occasionally, I was able to control the direction of his thoughts as he wrote home to Velma.

On one occasion, he was describing for her a funny little French

woman who visited the hospital with a basket that always was filled with

cigarettes and candy.

"Last time" [he wrote], "she brought with her a boy whom she called..."

He paused, with pencil upraised, trying to recall the name.

A moment later, he looked down at the page and stared with astonishment. The words, "She called him Maurice," had been added below the unfinished line.

"I must be going daffy," he muttered. "I'd swear I didn't write that."

Behind him, I stood rubbing my hands in triumph. It was my first

successful effort to guide the pencil while his thoughts strayed

elsewhere.

Another time, he wrote to Velma:

- "I've a strange feeling, lately, that dear old Dick is near.

Sometimes, as I wake up, I seem to remember vaguely having seen him in

my dreams. It's as if his features were just fading from view."

He paused here long so long that I made another attempt to take advantage of his abstraction.

By an effort of the will that it is difficult to explain, I guided his hand into the formation of the words:

- "With a jugful of kisses for Winkie, as ever her...."

Just then. Louis looked down.

"Good God!" he exclaimed, as if he had seen a ghost.

"Winkie" was a pet name I had given Velma when we were children together.

Louis always maintained there was no sense in it, and refused to

adopt it, though I frequently called her by the name in later years. And

of his own volition, Louis would never have mentioned anything

convivial as a jugful of kisses.

So, through the weary months before he was invalided home, I

worked. When he left France at the debarkation point, he still walked on

crutches, but with the promise of regaining the unassisted use of his

leg before very long. Throughout the voyage, I hovered near him, sharing

his impatience, his longing for the one we both held dearest.

Over the exquisite pain of the reunion—at which I was present,

yet not present—I shall pass briefly. More beautiful than ever, more

appealing with her vivid, deep coloring, Velma in the flesh was a vision

that stirred my longing into an intense flame.

Louis limped painfully down the gangplanks. When they met, she

rested her head silently on his shoulder for a moment, then—her eyes

brimming with tears—assisted him with the tender solicitude of a mother,

to the machine she had in waiting.

Two months later they were married. I felt the pain of this less

deeply than I would have done had it not been essential to my design.

Whatever vague nope I may have had. however, of vicariously

enjoying the delights of love were disappointed. I could not have

explained why—I only knew that something barred me from intruding upon

the sacred intimacies of their life, as if a defensive wall were

interposed. It was baffling, but a very present fact, against which I

found it useless to rebel, I have since learned—but no matter. * * *

This had no bearing on my purpose, which hinged upon the ability I

was acquiring of influencing Louis' thoughts and actions--of taking

partial control of his faculties.

The occupation into which he drifted, restricted in choice as he

was by the stiffened leg, helped me materially. Often, after an

interminable shift at the bank, he would plod home at night with brain

so weak and benumbed that it was a simple matter to impress my will upon

him. Each successful attempt, too, made the next one easier.

The inevitable consequence was that in time Velma should notice his aberrations and betray concern.

"Why did you say to me, when you came in last night, "There's a

blue Billy-goat on the stairs—I wish they'd drive him out?" she demanded

one morning.

He looked down shamefacedly at the tablecloth.

"I don't know what made me say it. I seemed to want to say

it, and that was the only way to get it off my mind. I thought you'd

take it as a joke." He shifted his shoulders, as if trying to dislodge

an unpleasant burden.

"And was that what made you wear a necktie to bed?" she asked, ironically.

He nodded an affirmative. “I knew it was idiotic—but the idea

kept running in my mind. It seemed as if the only way I could go to

sleep was to give in to it. I don't have these freaks unless I'm very

tired."

She said nothing more at the time, but that evening she broached

the subject of his looking for an opening in some less sedentary

occupation―a subject to which she thereafter constantly recurred.

Then came a development that surprised and excited me with its possibilities.

Exhausted, drained to the last drop of his nerve-force, Louis was

returning late one night from the bank, following the usual month-end

overtime grind. As he walked from the carline, I hovered over him,

subduing his personality, forcing it under control, with the effort of

will I had gradually learned to direct upon him. The process can only be

explained in a crude way: It was as if I contended with him, sometimes

successfully, for possession of the steering-wheel of the human car that

he drove.

Velma was waiting when we arrived. As Louis' feet sounded on the

threshold of their apartment, she opened the door, caught his hands, and

drew him inside.

At the action, I felt inexplicably thrilled. It was as if some

marvelous change had come over me. And then, as I met her gaze, I knew

what that that change was.

I held her hands in real flesh-and-blood contact. I was looking at her with Louis' sight!

The shock of it cost me what I had gained. Shaken from my poise, I felt the personality I had subdued regain its sway.

The next moment, Louis was staring at Velma in bewilderment. Her eyes were filled with alarm.

"You—you frightened me!" she gasped, withdrawing her hands, which I had all but crushed. "Louis, dear—don't ever look at me again like that!"

I can imagine the devouring intensity of gaze that had blazed forth from the features in that brief moment when they were mine.

From this time, my plans quickly took form. Two modes of action

presented themselves. The first and more alluring, however, I was forced

to abandon. It was none other than the wild dream of acquiring

exclusive possession of Louis' body--of forcing him down, out, and into

the secondary place I had occupied.

Despite the progress I had made, this proved inexpressibly

difficult. For one thing, there seemed an affinity between Louis' body

and his personality, which forced me out when he was moderately rested.

This bond I might have weakened, but there were other factors.

One was the growing conviction on his part that something was

radically wrong. With a faculty I had discovered of putting myself en rapport with him and reading his thoughts, I knew that at times he feared that he was going insane.

I once had the experience of accompanying him to an alienist and

there, like the proverbial fly on the wall, overhearing learned

scientific names applied to my efforts. The alienist spoke of "dual

personality," "amnesia," and "the subconscious mind," while I laughed in

my (shall I say) ghostly sleeve.

But he advised Louis to seek a complete rest and, if possible, to go into the country to build up physically— which was what I desired most to prevent.

I could not play the Mr. Hyde to his Dr. Jekyll if Louis maintained his normal virility.

Velma's fears, too, I knew were growing more acute. As

insistently as she could, without betraying too openly her alarm, she

pressed him to give up the bank position and seek work in the open

air—work that would prove less devitalizing to a person of his peculiar

temperament.

One of the results of debility from overwork is, apparently, that

it deprives the victim of his initiative—makes him fearful of giving up

his hold upon the meager means of sustenance that he has, lest he shall

be unable to grasp another. Louis was in debt, earning scarcely enough

for their living expenses, too proud to let Velma help as she longed to

do, his game leg putting him at a disadvantage in the industrial field.

In fact, he was in just the predicament I desired, but I knew that in

time her wishes would prevail.

The circumstances, however, that deprived me of all hope of

completely usurping his place was this: I could not, for any length of

time, face the gaze of Velma's eyes. The personified truth, the purity

that dwelt in them, seemed to dissolve my power, to beat me back into

the secondary relationship I had come to occupy toward Louis.

He was sometimes tempted to tell her: "You give me my one grip on sanity."

I have witnessed his panic at the thought of losing her, at the

thought that some day she might give him up in disgust at his

aberrations, and abandon him to the formless "thing" that haunted him.

Curious—to be of the world and yet not of it—to enjoy a

perspective that reveals the hidden side of effects, which seem so

mysterious from the material side of the veil. But I would gladly have

given all the advantages of my disembodied state for one hour of

flesh-and-blood companionship with Velma.

My alternative plan was this.

If I could not enter her world, what was to prevent me from bringing Velma into mine?

Daring? To be sure.

Unversed as I was in the laws that govern this mystery of passing

from the physical into another state of existence, I could only hope

that the plan would work. It might—and that was enough for me. I took a

gambler's chance. By risking all, I might gain all—might gain—

The thought of what I might gain transported me to a heaven of pain and ecstasy.

Velma and I—in a world apart—a world of our own—free from the

sordid trammels that mar the perfection of the rosiest earth-existence.

Velma and I—together through all eternity!

This much reason I had for hoping! I observed that other persons

passed through the change called death, and that some entered a state of

being in which I was conscious of them and they of me. Uninteresting

creatures they were, almost wholly preoccupied with their former

earth-interests; but they were as much in the world as I had been in the

world of Velma and Louis before that fragment of shrapnel ruled me out

of the game.

A few, it was true, on passing from their physical habitations,

seemed to emerge into a sphere to which I could not follow. This

troubled me. Velma might do likewise. Yet I refused to admit the

probability—refused to consider the possible failure of my plan. The

very intensity of my longing would draw her to me.

The gulf that separated us was spanned by the grave. Once Velma

had crossed to my side of the abyss, there would be no going back to

Louis.

Yet I was cunning. She must not come to me with overpowering

regrets that would cause her to hover about Louis as I now hovered about

her. If I could inspire her with horror and loathing for him—ah! if I

only could!

As a preliminary step, I must induce Louis to buy the instrument with which my

purpose was to be accomplished. This was not easy, for on nights when

he left the bank during shopping hours he was sufficiently vigorous to

resist my will. I could work only through suggestion.

In a pawnshop window that he passed daily I had noticed a

revolver prominently displayed. My whole effort was concentrated upon

bringing this to his attention.

The second night, he glanced at the revolver, but did not stop.

Three nights later, drawn by a fascination for which he could not have

accounted, he paused and looked at it for several minutes, fighting an

urge that seemed to command: "Step in and buy! Buy! Buy!"

When, a few evenings later, he arrived home with the revolver and

a box of cartridges that the pawnbroker had included in the sale, he

put them hastily out of sight in a drawer of his desk.

He said nothing about his purchase, but the next day Velma came across the weapon and questioned him regarding it

Visibly confused, he replied: "Oh, I thought we might need

something of the sort. Saw it in a window, and the notion of having it

sort of took hold of me. There's been a lot of housebreaking lately, and

it's just as well to be prepared."

And now with impatience I waited for the opportunity to stage my denouement

It came, naturally, at the end of the month, when Louis, after a

prolonged day's work, returned home, soon after midnight, his brain

benumbed with poring over interminable columns of figures. When his feet

ascended the stairs to his apartment it was not his faculties that

directed them, but mine—cunning, alert, aflame with deadly purpose.

Never was more weird preliminary to a murder-the entering, in

guise of a dear, familiar form, of a fiend incarnate, intent upon

destroying the flower of the home.

I speak of a fiend incarnate, even though I was that fiend, for I

did not enter Louis's body in full expression of my faculties. Taking

up physical life, my recollection of existence as a spirit entity was

always shadowy. I carried through the dominating impulses that had

actuated me on entering the body, but scarcely more.

And the impulse I had carried through that night was the impulse to kill.

With utmost caution, I entered the bedroom.

My control of Louis's body was complete. I felt, for perhaps the

first time, so corporeally secure that the vague dread of being driven

out did not oppress me.

The room was dark, but the soft, regular breathing of Velma,

asleep, reached my ears. It was like the invitation that rises in the

scent of old wine which the lips are about to quaff— quickening my

eagerness and setting my brain on fire.

I did not think of love. I lusted—but my lust to destroy that beautiful body—to kill!

However, I was cunning-cunning. With caution. I felt my way toward the desk and secured the revolver, filling its chambers with leaden emissaries of death.

When all was in readiness, I switched on the light.

She wakened almost instantly. As the radiance flooded the room, a

startled cry rose to her lips. It froze, unuttered, as—half rising—she

met my gaze.

Her beauty—the raven blackness of her hair falling over her bare

shoulders and full, heaving bosom, fanned the flame of my gory passion

into fury. In an ecstasy of triumph, I stood drinking in the picture.

While I temporized with the lust to kill—prolonging the exquisite sensation—she was battling for self-control.

"Louis!" The name was gasped through bloodless lips.

Involuntarily, I shrunk, reeling a little under her gaze. A

dormant something seemed to rise in feeble protest at what I sought to

do. The leveled revolver wavered in my hand.

But the note of panic in her voice revived my purpose. I laughed—mockingly.

"Louis!" her tone was sharp. but edged with terror. "Louis—put down that pistol! You don't know what you are doing."

She struggled to her feet and now stood before me. God! how beautiful—how tempting that bare white bosom!

"Put down that pistol!" she ordered hysterically.

She was frantic with fear. And her fear was like the blast of a forge upon the white heat of my passion.

I mocked her. A shrill maniacal laugh burst from my throat. She had said I didn't know what I was doing! Oh, yes, I did.

"I'm going to kill you!―kill you!" I shrieked, and laughed again.

She swayed forward like a wraith, as I fired. Or perhaps that was the trick played by my eyes as darkness overwhelmed me.

A few fragmentary pictures stand out in my recollection like clear-etched cameos on the scroll of the past.

One is of Louis, standing dazedly—slightly swaying as with

vertigo—looking down at the smoking revolver in his hand. On the floor

before him a crumpled figure in ebony and white and vivid crimson.

Then a confusion of frightened men and women in oddly assorted nondescrpt

attire—uniformed officers bursting into the room and taking the

revolver from Louis's unresisting hand—clumsy efforts at lifting the

white-robed body to the bed—a crimson stain spreading over the sheet—a

doctor, attired in collarless shirt and wearing slippers, bending over

her * * *

Finally, after a lapse of hours, a hushed atmosphere—efficient nurses—the beginning of delirium.

And one other picture—of Louis, cringing behind the bars of his

cell, denied the privilege of visiting his wife's bedside—crushed,

dreading the hourly announcement of her death—filled with unspeakable

horror of himself.

Velma still lived. The bullet had pierced her left lung and life

hung by a tenuous thread. Hovering near I watched with dispassionate

interest the battle for life. For the time I seemed emotionally spent. I

had made a supreme effort—events would now take their inevitable course

and show whether I had accomplished my purpose. I felt neither anxious

nor overjoyed, neither regretful nor triumphant—merely impersonally

curious.

A fever set in lessening Velma's slender chances of recovery. In

her delirium, her thoughts seemed always of Louis. Sometimes she

breathed his name pleadingly, tenderly, then cried out in terror at some

fleeting rehearsal of the scene in which he stood before her, the

glitter of insanity in his eyes, the leveled revolver in his hand. Again

she pleaded with him to give up his work at the bank; and at other

times she seemed to think of him as over on the battlefields of Europe.

Only once did she apparently think of me—when she whispered the name by which I had called her, "Winkie!" and added, "Dick!" But, save for this exception, it was always "Louis! Louis!"

Her constant reiteration of his name finally dispelled the apathy of my spirit.

Louis! All the vengeful fury toward him I had experience

when my soul went hurtling into the region of the disembodied returned

with thwarted intensity.

When Velma's fever subsided, when the long fight for recovery

began and she fluttered from the borderland back into the realm of the

physical, when I knew I had failed—balked of my prey, I had at least

this satisfaction:

Never again would these two—the man I hated and the woman for

whom I hungered—never again would they be to each other as they had been

in the past. The perfection of their love had been irretrievably

marred. Never would she meet his gaze without an inward shrinking.

Always on his part— on

both their parts—there would be an undercurrent of fear that the

incident might recur—a grizzly menace, poisoning each moment of their

lives together.

I had not schemed and contrived—and dared—in vain.

This was the thought I hugged when Louis was released from jail,

upon her refusal to prosecute. It caused me sardonic amusement when, in

their first embrace, the tears of despair rained down their cheeks. It

recurred when they began their pitiful attempt to build anew on the

shattered foundation of love.

And then—creepingly, slyly, like a bird of ill omen casting the shadow of its silent wings over the landscape—came retribution.

Many times, in retrospect, I lived over that brief hour of my

return to physical expression—my hour of realization. Wraithlike, arose a

vision of Velma—Velma as she had stood before me that night, staring at

me with horror. I saw the horror deepen—deepen to abject despair.

How beautiful she had looked! But when I tried to picture that

beauty, I could recall only her eyes. It mattered not whether I wished

to see them—they filled my vision.

They seemed to haunt me. From being vaguely conscious of them, I

became acutely so. Disconcertingly, they looked out at me from

everywhere—eyes brimming with fear—eyes fixed and staring—filled with

horrified accusation.

The beauty I had once coveted became a thing forbidden, even in

memory. If I sought to peer through the veil as formerly—to witness her

pathetic attempts to resume the old life with Louis—again those eyes!

It may perhaps sound strange for a disembodied creature—one whom

you would call a ghost—to wail of being haunted. Yet haunting is of the

spirit, and we of the spirit world are immeasurably more subject to its

conditions than those whose consciousness is centered in the material

sphere.

God! Those eyes. There is a refinement of physical torture which

consists of allowing water to fall, drop by drop, for an eternity of

hours, upon the forehead of the victim. Conceive of this torture

increased a thousandfold, and a faint idea may be gained of the torture

that was mine—from seeing everywhere, constantly, interminably, two orbs

ever filled with the same expression of horror and reproach.

Much have I learned since entering the Land of the Shades. At

that time I did not know, as I know now, that my punishment was no

affliction from without, but the simple result of natural law. Cause set

in motion must work out their full reaction. The pebble, cast into a

quiet pool, makes ripples which in time return to the place of their

origin. I had cast more than a pebble of disturbance into the harmony of

human life, and through my intense preoccupation in a single aim had

delayed longer than usual the reaction. I had created for myself a hell.

Inevitably I was drawn into it.

Gone was every desire I had known to hover near the two who had

so long engrossed my attention. Haunted, harried by those dreadful

accusers, I sought to fly from them to the ends of the earth. There was

no escape, yet, driven frantic, I still struggled to escape, because

that is the blind impulse of suffering creatures.

The emotions that had so swayed me when I tried to blast the

lives of two who held me dear now seemed puny and insignificant in

comparison with my suffering. No physical torment can be likened to that

which engulfed me until my very being was but a seething mass of agony.

Through it, I hurled maledictions upon the world, upon myself, upon

the. creator. Horrible blasphemies I uttered.

And, at last—I prayed.

It was but a cry for mercy—the inarticulate appeal of a tortured

soul for surcease of pain—but suddenly a great peace seemed to have come

upon the universe.

Bereft of suffering, I felt like one who has ceased to exist.

Out of the silence came a wordless response. It beat upon my consciousness like the buffeting of the waves.

Words

known to human ears would not convey the meaning of the message that

was borne upon me—whether from outside source or welling up from within,

I do not know. All I know is that it filled me with a strange hope.

A thousand years or a single instant—for time is a relative

thing—the respite lasted. Then, I sank, as it seemed, to the old level

of consciousness, and the torment was renewed.

Endure it now I knew that I must—and why. A strange new purpose

filled my being. The light of understanding had dawned upon my soul.

And so I came to resume my vigil in the home of Velma and Louis.

A brave heart was Velma's一dauntless and true.

With the effects of the tragedy still apparent in her pallor and

weakness, and in the shaken demeanor and furtive, self-distrustful

attitude of Louis, she yet succeeded in finding a place for him as

overseer of a small country estate.

I have said that I ceased to feel the torment of passion for

Velma in the greater torment of her reproach. Ah!-but I had never ceased

to love her. As I now realized, I had desecrated that love, had

transmuted it into a horrible travesty, had, in my abysmal ignorance,

sought to obtain what I desired by destroying it; yet, beneath all, I

had loved.

Well I know, now that had I succeeded in my intention toward her,

Velma would have ascended to a sphere utterly beyond my comprehension.

Merciful fate had diverted my aim—had made possible some faint

restitution.

I returned to Velma, loving her with a love that had come into its own, a love unselfish, untainted by thought of possession.

But, to help her, I must again hurt her cruelly.

Out of the chaos of her life she had slowly restored a semblance

of harmony. Almost she succeeded in convincing Louis that their old

peaceful companionship had returned; but to one who could read her

thoughts, the nightmare thing that hovered between them weighed cruelly

upon her soul.

She was never quite able to look into her husband's eyes without a

lurking suspicion of what might lie in their depths; never able to

compose herself for sleep without a tremor lest she should wake to find

herself confronted by a fiend in his form. I had done my work only too

well!

Now, slowly and inexorably, I began again undermining Louis'

mental control. The old ground must be traversed anew, because he had

gained in strength from the respite I had allowed him, and his outdoor

life gave him a mental vigor with which I had not been obliged to

contend before. On the other hand, I was equipped with new knowledge of

the power I intended to wield.

I shall not relate again the successive stages by which I

succeeded, first in influencing his will, then in partially subduing it,

and, finally, in driving his personality into the background for

indefinite periods. The terror that overwhelmed him when he realized

that he was becoming a prey to his former aberrations may be imagined.

To shield Velma, I performed my experiments, when possible, while

he was away from her. But she could not long be unaware of the

moodiness, the haggard droop of his shoulders which accompanied his

realization that the old malady had returned. The deepening terror in

her expression was like a scourge upon my spirit—but I must wound her in

order to cure.

More than once, I was forced to exert my power over Louis to

prevent him from taking violent measures against himself. As I gained

the ascendancy, a determination to end it all grew upon him. He feared

that unless he took himself out of Velma's life, the insanity would

return and force him again to commit a frenzied assault upon the one he

held most dear. Nor could he avoid seeing the apprehension in her manner

that told him she knew—the shrinking that she bravely tried to conceal.

Though my power over him was greater than before, it was

intermittent. I could not always exercise it. I could not, for example,

prevent his borrowing a revolver one day from a neighboring farmer, on

pretense of using it against a marauding dog that had lately visited the

poultry yard.

Though I knew his true intention, the utmost that I could do—for

his personality was strong at the time—was to influence him to postpone

the deed he contemplated.

That night, I took possession of his body while he slept. Velma

lay, breathing quietly, in the next room—for as this dreaded thing came

upon him they had, through tacit understanding, come to occupy separate

bedrooms.

Partially dressing. I stole downstairs and out to the tool-shed

where Louis—fearing to trust it near him in the home--had hidden the

revolver. As I returned, my whole being rebelled at the task before

me—yet it was unavoidable, if I would restore to Velma what I had

wrenched from her.

Quietly though I entered her room, a gasp—-or rather a quick, hysterical intake of breath—warned me that she had wakened.

I flashed on the light.

She made no sound. Her face went white as marble. The expression

in her eyes was that which had tortured me into the depths of a hell

more frightful than any conceived by human imagination.

A moment I stood swaying before her, with leveled revolver—as I had stood on that other occasion, months before.

Slowly, I lowered the revolver, and smiled—not as Louis would

have smiled but as a maniac formed in his likeness, would have smiled.

Her lips framed the word "Louis," but, in the grip of despair,

she made no sound. It was the despair not merely of a woman who felt

herself doomed to death, but of a woman who consigned her loved one to a

fate worse than death.

Still I smiled—with growing difficulty, for Louis' personality was restive and my time in the usurped body was short.

In that moment, I was not anxious to give up his body. At this

new glimpse of her beauty through physical sight, my love for Velma

flamed into hitherto unrealized intensity. For an instant my purpose in

returning was forgotten. Forgotten was the knowledge of the ages which I

had sipped since last I occupied the body in which I faced her.

Forgotten was everything save—Velma.

As I took a step forward, my arms outstretched, my eyes expressing God knows what depth of yearning, she uttered a scream.

Blackness surged over me. I stumbled. I was being forced

out—out—That cry of terror had vibrated through the soul of Louis and he

was struggling to answer it.

Instinctively, I battled against the darkness, clung to my hard-won ascendancy. A moment of conflict, and again I prevailed.

Once more I smiled. The effect of it must have been weird, for I

was growing weaker and Louis had returned to the attack with

overwhelming persistence. My tongue strove for expression:

"Sorry—Winkie—it won't happen again—I'm not—coming—back——"

When

I recovered from the momentary unconsciousness that accompanies

transition from the physical to spiritual, Louis was looking in affright

at the huddled figure of Velma, who had fainted away. The next instant,

he had gathered her in his arms.

Though I had come near failing in the attempt to deliver my

message, I had no fear that my visit would prove in vain. With clear

prescience, I knew that my utterance of that old familiar nickname, "Winkie,"

would carry untold meaning to Velma—that hereafter she would fear no

more what she might see in the depths of her husband's eyes--that with a

return of her old confidence in him, the specter of apprehension would

be banished forever from their lives.

About the Author

Willard E. Hawkins was born on September 27, 1887, in Fairplay, Colorado. He was an author, editor, publisher, and public speaker with stories in

Amazing Stories,

Astounding Science-Fiction,

The Blue Book Magazine,

Breezy Stories,

The Cavalier,

Chicago Ledger,

Fantastic Adventures,

The Green Book Magazine,

Imagination,

The Red Book Magazine,

Science Fiction,

Super Science Novels,

Thrilling Wonder Stories,

Western Outlaws,

Western Rangers, and

Western Trails.

Hawkins also worked as an editor with the Loveland Reporter (at age nineteen), Denver Times, Rocky Mountain News, Rocky Mountain Hotel Bulletin, and American Greeter.Hawkins established The Student Writer magazine in 1916. He was also an editor, with David Raffelock, of The Author and Journalist, which may have been an outgrowth of The Student Writer. Among those who read and benefitted from The Author and Journalist was Erle Stanley Gardner (1889-1970), later creator of Perry Mason. Hawkins died on April 17, 1970, presumably in Craig, Colorado. The

current National Writers Association is descended from The Writers

Colony in the Rocky Mountains, founded by Raffelock in 1929.

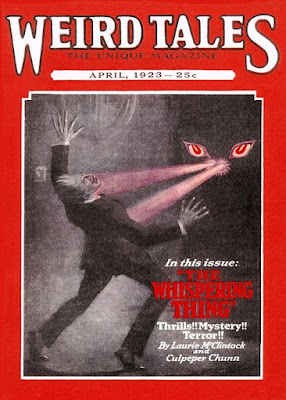

![Weird Tales v01n03 [1923-05] Weird Tales v01n03 [1923-05]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh_SCBdu-JjGh9fzdqw9DVuoeB7VaBnJbJvHNDJu6ug-DYwFTmnOhuyKIT6oMRu37DYPGCRPNZKENwFQL1qNuXy_xX-B7Ve-3ukEocJ5IIjIIdUVv_Ipn7OHPhImqZC8xP4jLmnt4CxtdavS02DxPBK-GmvKawzlo0uOSxYlBoS9qDcAzI_d5VsxQ/w285-h400/Screenshot_20230405_054120.jpg)

.jpg)